By Dan Sherven

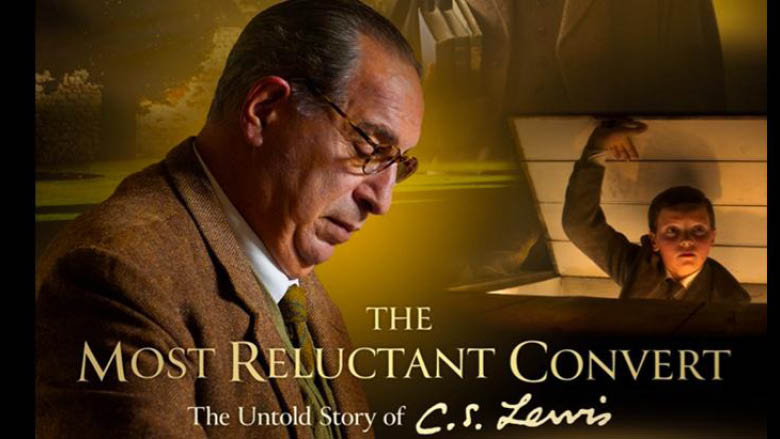

The Most Reluctant Convert is a new film about Christian writer C.S. Lewis’ life. The film focuses on his conversion from atheism to Christianity. As Lewis says in the film, “perhaps you’ve read my books. [The Chronicles of Narnia:] The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is the most famous. But there’s one story that’s not so well-known. It’s my story.”

Max McLean wrote the original play, which the movie is based on. He is also Founder and Artistic Director of the Fellowship for Performing Arts, a New York theatre. In the film, McLean plays C.S. Lewis as an old man. “People read him still,” McLean says. “He’s sold 250 million books.”

Fellowship for Performing Arts is a Christian theatre. “Our mission is to produce theatre from a Christian worldview to engage a diverse audience,” McLean says. “And by diverse, we mean worldview diversity.” The play and film are based on C.S. Lewis’ autobiography Surprised by Joy.

“I transcribed [Lewis’ autobiography],” McLean says. “Because I wanted to get inside how he makes choices, how he goes one way or the other. That really helped me understand his sense of humour, his massive vocabulary, and the way he turned phrases — [it] was just exciting and extraordinary.”

“Once I did that, it was really a matter of editing it down to a story that would trace Lewis’ conversion from vigorous debunker of Christianity to perhaps becoming the most influential Christian writer of the 20th century,” McLean says.

McLean also adapted Lewis’ books The Screwtape Letters and The Great Divorce for the stage. “What keeps me going back to him is that he challenges people’s assumptions about reality. He read everything from the Greeks to the moderns, had a steel-trap mind that remembered everything he read, and could translate it into amazing prose and speech. And did it all from a Christian perspective.”

McLean recommends studied atheists consider Lewis’ books The Problem of Pain and Miracles. And for someone more interested in Lewis’ imagination: The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, and his space trilogy.

“One of his great statements was that imagination is the organ of meaning; reason is the organ of truth,” McLean says. “And I think what Lewis meant by that is the imagination serves up the raw material of what we think about. If an idea doesn’t capture your imagination, doesn’t register as important or significant, it’s not going to trigger the desire to find out more. And Lewis has been doing that for me for a long time.”

McLean suggests that if a person is not satisfied with the secular worldview; that your existence is “atoms colliding in your skull,” and a person also has an interest in the supernatural, there is “the theory that Lewis has, that we come from someplace else.

“That we’re not the product of the idiocy of the universe. But we were dropped by a fuller, more perfect life. And ultimately, we will go back to that. That’s the Christian theory. And Lewis in all his writings expresses that in a way that’s compelling and imaginative.”

McLean says that in the film, “Lewis is an older man coming alive in his memories, looking back on the events that led to his conversion from atheism. First, belief in God, and finally, to belief in Christ. And the film details the steps he took from being a vigorous debunker of Christianity until what he says in the script, that he finally gave in. And that God was God; [Lewis] knelt and prayed.”

McLean did not find it easy to play Lewis in the film: “Playing someone so much smarter than you, that has a better vocabulary than you do, that expresses himself better than you do, that’s really stretching. But I also was aware of the responsibility because so many people consider Lewis a kind of spiritual guide.”

Yet McLean doesn’t think Lewis would be too thrilled about the film. “He didn’t have much time for drama. He went to plays, and he liked the theatre, but he never wrote for the theatre. I think he would think [the film] was a lot of bother.”

And McLean says in the last years of Lewis’ life, Lewis told his lawyer: “Five years after I’m gone, no one will read a word I write.” McLean adds, “I think he would be shocked at the amount of attention that’s paid to him.”

McLean thinks if he met Lewis in the afterlife, “first I would be awed by him so I might be tongue-tied to begin with. But after that’s done, I’m sure I’d have a million questions about his journey, especially as it relates to his conversation with Tolkien that prompted [Lewis] to believe in Jesus.”

McLean says Lewis first abandoned atheism for the “god of the philosophers.” An impersonal god behind reality. Then Lewis had “a belief in God, meaning the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. It was the God of the burning bush. It was the God that brought The Ten Commandments down from the fiery mountain on Mount Sinai. That was the God he bowed down to.

“But he made a very clear point that (that) God was not human. He had no belief in the Incarnation at all. So going from that step to belief in Christ was a pretty significant step, and I’d like to talk with him about that.”

It is no surprise Lewis’ autobiography is called Surprised by Joy. As McLean says, “what drove his journey was a thing he called joy which has to be distinct from happiness or pleasure. This sense of joy was the central story of his life. There’s a quote; he called it a desire, a desire for something this world can’t offer.”

If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world. – C.S. Lewis

The Most Reluctant Convert: The Untold Story of C.S. Lewis is available for in-home viewing today. Find out more at https://cslewismovie.com/

|

Dan Sherven is an author from Regina, SK. |